Feeling stressed? Don't sweat. There's good evidence to suggest that your body will be pumping out its own “homegrown” cannabinoid compounds that help to chill you out.

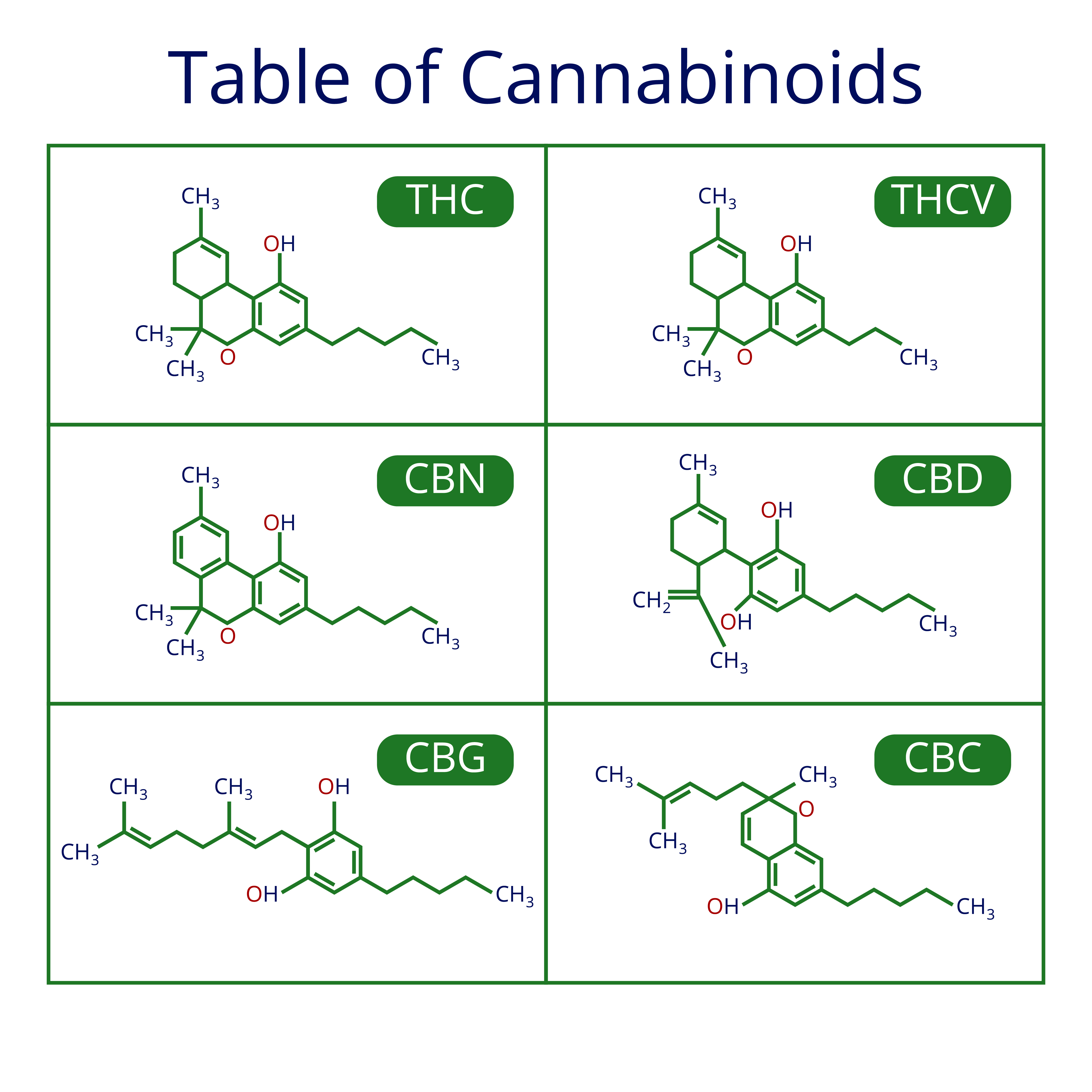

You might be surprised to hear that the human body naturally produces chemicals that are very similar to delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, better known as THC, the psychoactive compound in cannabis, as well as cannabidiol (CBD).

Known as endocannabinoids, these compounds were only identified in 1992 and they remain little understood by scientists. However, there’s emerging evidence that may have a profound role in many bodily functions, from learning and memory, to pain control and immune responses.

It isn’t just humans that produce endocannabinoids either – scientists believe they are produced by all vertebrate species and likely evolved millions of years before the emergence of cannabinoids produced by the plant Cannabis sativa.

In a new study, scientists at Northwestern University found that stressed-out mice release endocannabinoids in the brain’s emotional hub, the amygdala. In turn, the compounds dampen the incoming stress signals coming from the hippocampus, a region of the brain linked to memory and emotion.

To prove their point, the scientists then “switched off” the cannabinoid receptors (CB1) in the brains of the mice. This appeared to reduce their ability to cope with the stress. After they were exposed to stress, they had a reduced preference for their sugary liquid treat, which the researchers say relates to the decrease in pleasure often seen in people with stress-related disorders.

Once again, this phenomenon has only been identified in mice so far. However, the researchers suggest it most likely will apply to humans and, if so, it could show the way to new avenues of treating stress-related psychiatric disorders.

“Understanding how the brain adapts to stress at the molecular, cellular and circuit level could provide critical insight into how stress is translated into mood disorders and may reveal novel therapeutic targets for the treatment of stress-related disorders,” Sachin Patel, corresponding study author and the chair and a psychiatrist at Northwestern Medicine, said in a statement.

“Determining whether increasing levels of endogenous cannabinoids can be used as potential therapeutics for stress-related disorders is a next logical step from this study and our previous work,” Patel added. “There are ongoing clinical trials in this area that may be able to answer this question in the near future.”

The study is published in the journal Cell Reports.